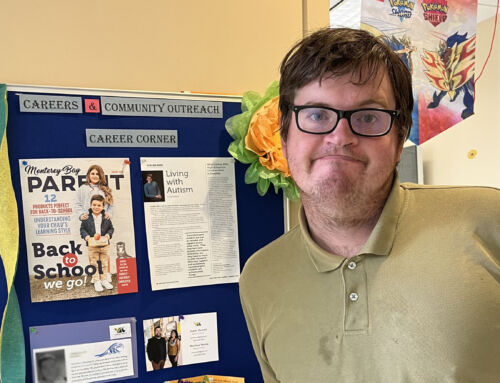

By Amy Jenkins, Academic Tutor CLE Austin

The dreaded Speech class is often a core requirement in either high school or college – or both. Nowadays, the aim in these classes is less hyper-focused on how to stand in front of a crowd and speak and more generally addresses communication in all forms: how to navigate a disagreement with a friend, how to write an email to a boss, professor, or colleague… as well as how to stand in front of a crowd and speak. All in all, it’s a class about interacting with others, and every news outlet out there today has a story about how long-lasting and beneficial the lessons learned in these classes can be.

So, what do we do when the class about communicating with others very much neglects – or, in some cases, maligns–-those who society perceives as “other”?

My student Chris and I began noticing these often subtextual norms right in chapter one of the text and kept noticing them as the class went on. Not only did the implied “everybody” not have room for the neurodiverse, it also did not have room for people with disabilities or the LGBTQ community. There were occasions where certain cases were mentioned, such as a sidebar discussing deafness and hearing disabilities in the chapter on listening, but the text’s definition of listening was “a process of recognizing…the messages you hear.” This group of people were addressed, yes, but not as if they might be both a part of that group and a student in the class.

When I asked her to discuss the general impression this class has left on her for this article, Chris noted that while the book was seldom overt, it had a persistent undercurrent, “constantly putting the people misunderstood in the wrong.”

Until that happens, it’s very much down to the luck of the draw for students on what educators they have when reading these kinds of texts. Someone needs to be there to take on that leadership role (a topic that is covered in not just one chapter, but an entire unit of Chris’ textbook) and let students know that not only should they do better when thinking and speaking about “everyone”—but that they can.